Using Norwegian Kveik: Old Yeast, New Tricks

It seems like everyone these days is talking about Norwegian kveik yeasts, due to the promise of fast, clean, and hot fermentations beyond what we thought was possible for beer production. We’ve found that people tend to fall into two camps when it comes to kveik: the converts, and the skeptics. The aims of this article are to provide more information to the converts to expand the types of beers they produce with kveik, and also provide a convincing argument for the kveik-skeptics to also learn a bit more and give these fascinating yeasts a try.

A sampling of original kveik yeasts (both liquid and dry in this case)

Kveik yeasts are now available through several different yeast companies, who have been intrigued by the surprising characteristics of these yeasts. Back in 2016, we sourced some original kveik cultures from Lars Marius Garshol, the beer writer who has been critical in highlighting and preserving surviving European farmhouse brewing traditions.

Map of kveik source locations

Kveik is used to produce traditional Norwegian farmhouse beers, mostly centring on two brewing regions south and north of the Jostedal glacier in the fjords of western Norway. In the south, centred on Voss, the beers are a caramel-brown with deep citrus and caramel flavour, from both the use of long boils as well as the regional kveik. In the north, centred on Hornindal, the beers are often ‘raw ales’, not boiled at all. These beers are lighter and brighter in flavour, and some acidity is not necessarily considered an off-flavour. The kveik in this region can contribute to tropical fruit and orchard aromas. Everywhere, juniper persists, infused in all of the brewing water and lending a decidedly boreal edge to the regional beers. I am radically simplifying things of course, since farmhouse brewing is quite family-dependent too.

A flake of dried kveik yeast shows good viability when rehydrated, and can start fermenting wort very quickly.

Once we got kveik into the lab, what we found astounded us - the dry yeast, when rehydrated, began fermenting within an hour. What was more, the yeast seemed to produce clean, fruity beers. We were immediately captivated and were able to start to conduct some proper scientific research in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Guelph (George van der Merwe, Caroline Tyrawa) as well as VTT in Finland (Kristoffer Krogerus).

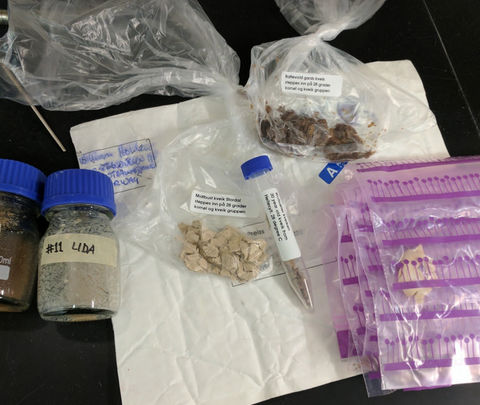

The original Kveik cultures contain multiple Saccharomyces cerevisiae 'strains'. WLN agar is used here to differentiate strains based on colony morphology.

It’s important to distinguish between kveik isolates and the original cultures. The original cultures typically contain multiple strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and some original kveik cultures contain a large strain diversity. Some kveik cultures do contain bacteria, mostly lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus) and acetic acid bacteria (Gluconobacter). In the lab and commercially, we work with kveik isolates, pure cultures originating from the original yeast material. Some of our products are blends of high-performing isolates from the original cultures, and all are bacteria-free. This appears to be true of most commercially available kveik cultures.

In the lab, we were able to confirm some of the interesting qualities of kveik: they do indeed perform very well under high temperature (40ºC) and high alcohol (16%) environments, they ferment faster than several industrial beer strains, they produce less fusel alcohol at high temperature, they are non-phenolic, and they can produce noticeable amounts of fruity esters (pineapple, apple, floral). That was really fascinating because it suggested these yeasts could be used to replace English or American strains in beer styles typically employing those yeasts.

The yeast family tree with a Nordic twist. Kveik has two 'haplotypes' (genetic origins), one within the standard European brewing yeast group and another more mysterious parent.

We also got to dive deep into the genetics of kveik yeasts and made another surprising finding. The kveik yeast family appears to be a hybrid of a distant ancestor of the main brewing yeast group (think German Ale, English Ale, and American Ale strains) along with a mysterious ancestor, that may have roots as far back as Asia. So in addition to having unique fermentation traits, kveik also appears to be genetically distinct from other brewing yeasts as well.

It is still unclear what genetic mutations give rise to the behaviour of kveik, but this is something we are actively pursuing now. We did find several mutations in kveik that were not found in any other beer yeasts, some of which may be related to temperature tolerance or fermentation rate.

That’s all well and good, but as a brewer, how do I use kveik? Do the usual rules apply to yeast that breaks a lot of rules?

In general, kveik can be used like regular yeast. It can ferment anywhere from 15 to 40 ºC. Underpitching has been reported to result in fruitier flavours, but slightly slower fermentations. Increasing temperature also has been reported to produce a fruitier beer. Repitching is typically problem-free as this yeast has adapted to being dormant for long periods of time. These process controls are now being explored in the lab and we are hoping to be able to help brewers dial in precise flavour profiles with kveik in the future.

When Ebbegarden Kveik and our Vermont Ale were used in a NEIPA, the resulting sensory profile was nearly the same. This isn't a bad thing! Brewers are looking to tweak this style to make it their own.

Since kveik are non-phenolic and range in character from neutral to fruity (depending on strain and handling), they can be used for a wide range of styles. While we encourage brewers to experiment with reproducing the traditional styles to understand the traditional context for kveik, we recognize these yeasts are also catching on in more popular and trendy beer styles, like NEIPAs. The enhanced fruitiness of kveik and low potential for fusel alcohols and diacetyl can help to produce heavily dry-hopped beers with less worry.

Kveik yeast is not a panacea and will not solve every brewing problem, but we do think these yeasts will settle into a role as another tool in our ever-expanding beer fermentation toolset. To date, very few of the known kveik yeasts have been commercialized, and fewer still have been studied in detail in research laboratories. We think there is still lots to learn from these surprising landrace yeasts, and that they will expand our brewing flavour possibilities and also help us understand more about yeast domestication and stress adaptation. Through the continued drive of craft brewers to explore new ideas, we will be able to teach these old yeasts new tricks.

A plea:

If you are using kveik, please make mention of the original source of the kveik. Many of the farmhouse brewers have graciously offered these yeasts for science and commercialization, and it is important to give credit where it is due to the farmers who kept traditional yeast alive.

For more information:

Garshol, L. M., and Preiss, R. (2018). How to Brew with Kveik. Tech. Q. 55, 76–83. doi:10.1094/TQ-55-4-1211-01.

Preiss, R., Tyrawa, C., Krogerus, K., Garshol, L. M., and Van Der Merwe, G. (2018). Traditional Norwegian Kveik are a Genetically Distinct Group of Domesticated Saccharomyces cerevisiae Brewing Yeasts. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2137.

Kveik registry